Brown University

In pursuit of batteries that deliver more power and operate safely, researchers are working to replace the liquids used in today’s lithium-ion batteries with solid materials. A research team from Brown University and the University of Maryland developed new material for use in solid-state batteries that’s derived from an unlikely source: trees.

In research published in the journal Nature, a solid ion conductor combines copper with cellulose nanofibrils — polymer tubes derived from wood. The paper-thin material has an ion conductivity that is 10 to 100 times better than other polymer ion conductors, the researchers say. It could be used as either a solid battery electrolyte or as an ion-conducting binder for the cathode of an all-solid-state battery.

“By incorporating copper with one-dimensional cellulose nanofibrils, we demonstrated that the normally ion-insulating cellulose offers a speedier lithium-ion transport within the polymer chains,” University of Maryland’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering professor Liangbing Hu says. “In fact, we found this ion conductor achieved a record high ionic conductivity among all solid polymer electrolytes.”

The work was a collaboration between Hu’s lab and the lab of Yue Qi, a professor at Brown’s School of Engineering.

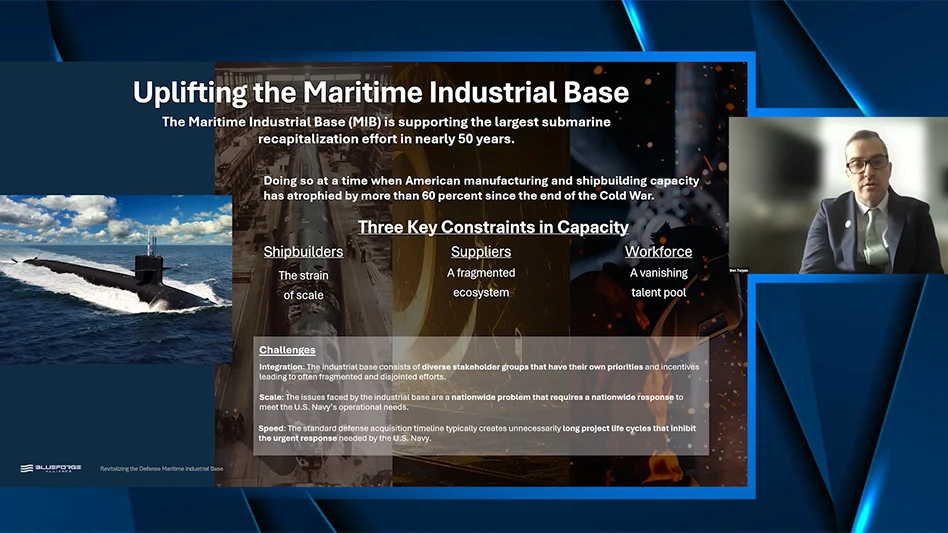

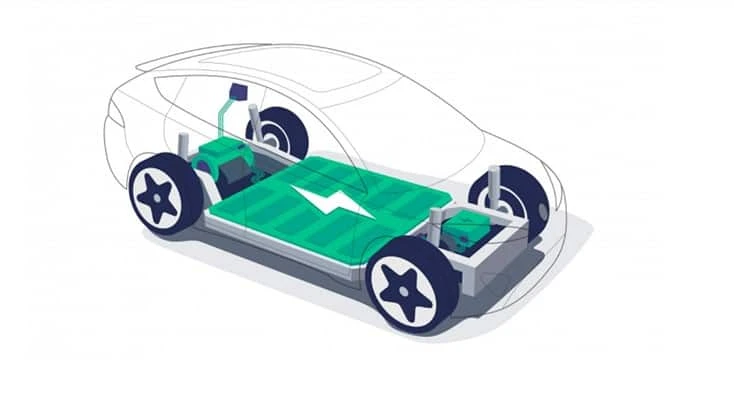

Today’s lithium-ion batteries, used in everything from cellphones to cars, have electrolytes made from lithium salt dissolved in a liquid organic solvent. The electrolyte conducts lithium ions between a battery’s cathode and anode. Liquid electrolytes work, but they have some downsides. At high currents, tiny filaments of lithium metal(dendrites) form in the electrolyte leading to short circuits. Liquid electrolytes are made with flammable and toxic chemicals.

Solid electrolytes prevent dendrite penetration and can be made from non-flammable materials. Most of the solid electrolytes investigated are ceramic materials, which conduct ions but they’re also thick, rigid, and brittle. Stresses during manufacturing and charging and discharging can lead to cracks and breaks.

The material introduced in this study is thin and flexible, like a sheet of paper, and conductively on par with ceramics.

Qi and Qisheng Wu, a senior research associate at Brown, performed computer simulations of the microscopic structure of the copper-cellulose material to understand why it is able to conduct ions so well. The modeling study revealed the copper increases the space between cellulose polymer chains, normally existing in tightly packed bundles. The expanded spacing creates ion superhighways which lithium ions can zip by relatively unimpeded.

“The lithium ions move in this organic solid electrolyte via mechanisms that we typically found in inorganic ceramics, enabling the record high ion conductivity,” Qi said. “Using materials nature provides will reduce the overall impact of battery manufacture to our environment.”

The new material acts as a cathode binder for a solid-state battery while also working as a solid electrolyte. To match the capacity of anodes, cathodes need to be substantially thicker. That thickness can compromise ion conduction, reducing efficiency. For thicker cathodes to work, they need to be encased in an ion-conducting binder. Using their new material as a binder, the team demonstrated one of the thickest functional cathodes ever reported.The researchers are hopeful that the new material could be a step toward bringing solid state battery technology to the mass market.The research at Brown University was supported by the National Science Foundation (DMR-2054438).

Latest from EV Design & Manufacturing

- Powering homes with EV batteries could cut emissions, save thousands of dollars

- Meviy introduces stainless steel passivation option for CNC, sheet metal parts

- December Lunch + Learn webinar with Fagor Automation

- December Lunch + Learn webinar with LANG Technik + Metalcraft Automation Group

- EVIO makes public debut with hybrid-electric aircraft

- Redesigned pilot step drill triples performance

- Green Energy Origin expands battery electrolyte manufacturing in North America, Europe

- What’s next for the design and manufacturing industry in 2026?